In 1996, when California voters passed Proposition 209, they did not end affirmative action. The California Civil Rights Initiative only prohibited the use of racial and ethnic preferences in state employment, education and contracting. Despite the new law, such preferences continued.

Former army captain Jair Bolsonaro is the favorite to win Brazil’s runoff presidential election on October 27th. Given his disparaging comments based on race, gender and sexual identity in the past, his support for military involvement in law and order issues, and his sometimes flippant characterizations of liberal democracy, his likely triumph has triggered an international outcry.

To judge by some of the comments, there is a temptation, since Bolsonaro’s stunning first-round victory over left-wing candidate Fernando Haddad, a crony of former leftist President Lula da Silva (now jailed on corruption charges), to think some kind of cultural radicalism or religious obscurantism is making Brazilian voters prone to right-wing populism. This is to misunderstand the essence of illiberal populism.

Populism is usually a disease of democracy, a sentiment that grows within a democratic system but seeks to brush aside the rule of law by replacing it with a superior legitimacy that comes from the bond established between the savior and the masses. Very specific, traumatic circumstances drive voters to seek solutions they would otherwise not seek. It is not that Brazilians are particularly prone to right-wing populism. When Venezuelans first voted for Hugo Chávez in 1998, they didn’t vote for a left-wing populist because they were ontologically predisposed to it, but because an accumulation of grievances had modified the parameters of the reasonable.

The U.S. government’s Conservation Reserve subsidy program started with the best of intentions.

Responding to a short-term plunge in crop prices in the mid-1980s, the U.S. government offered distressed farmers a temporary subsidy payment if they would take some of their cropland out of production and plant trees instead. Farmers would benefit from the income from the subsidy and from higher crop prices from the reduced supply of crops they continued to grow. Then, after the planted trees matured, the farmers who also became foresters would be able to harvest the timber they had grown and would have a new source of income. Meanwhile, taking the cropland out of production in this way would benefit the environment by reducing erosion in ecologically sensitive areas.

It seems like a winning scenario. Unfortunately, the program became a boondoggle, where the farmers who went along with it are now facing a plunge in prices for their timber crop, echoing the very problem that launched them onto their subsidy-dependent path. The Wall Street Journal reports:

When others do it, it’s terrorism; when Americans do it, it’s national defense.

When others do it, it’s a war crime; when Americans do it, it’s collateral damage.

When others do it, it’s torture; when Americans do it, it’s enhanced interrogation.

When others do it, it’s unprovoked attack; when Americans do it, it’s shock and awe.

When others do it, it’s imperialism; when Americans do it, it’s global defense of freedom.

When others do it, it’s lying propaganda; when Americans do it, it’s breaking news on CNN.

When others do it, they go to hell; when American do it, they go to heaven.

***

Robert Higgs is Senior Fellow in Political Economy at the Independent Institute, author or editor of over fourteen Independent books, and Editor at Large of Independent’s quarterly journal The Independent Review.

In all the annals of really bad decisions made in the pursuit of political benefit, President Obama’s 2010 federal government takeover of the student loan industry from the private sector has to rank among both the worst and the most costly.

How do we know? Here’s how Cory Turner of National Public Radio recently described what has become the modern day role of the U.S. Department of Education:

“Today, the U.S. Department of Education is, essentially, a trillion-dollar bank, serving more than 40 million student borrowers.”

The Federal Reserve puts the numbers at 44.5 million student loan borrowers with a combined student loan debt liability of $1.5 trillion. Meanwhile, the U.S. government has cumulatively borrowed about $1.2 trillion to fund its Federal Direct Student Loan Program, with nearly $1 trillion of that total having been borrowed since President Obama put the U.S. Department of Education into the student loan business in March 2010.

[This post was co-authored by D.J. Deeb.]

With much unintended irony, Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker signed legislation in June that the state legislature and the press heralded as a “Grand Bargain.” This new law increases the state minimum wage, creates a paid family and medical leave program, implements an annual two-day sales tax holiday, and eliminates the requirement that retailers pay time-and-a half to workers on Sundays and holidays. Unfortunately, it will only drive businesses away from Massachusetts and hurt the very workers that it aims to benefit.

The so-called grand bargain was made in order to get rid of a number of ballot initiatives in November’s election. Labor unions supported a ballot initiative to raise the minimum wage from $11 to $15 an hour in a series of increases over four years. The grand bargain instead phases this same increase in over five years.

Unions supported a ballot initiative for paid family and medical leave. The grand bargain gives it to them. It creates a program that permits almost all employees to take up to 12 weeks of paid family leave and up to 20 weeks of paid medical leave while returning to their same or similar position with the same employee pay and benefits. It’s funded with a 0.63 percent payroll tax paid by employers and workers that will average around $4.50 weekly per employee.

DuBois is not one of my favorite historical figures but he is essentially right on this point. One could add that states rights or the rights of the states is not even mentioned in the secessionist declarations of South Carolina and Mississippi. Essentially, the main theory these documents put forward was the Northern states had violated the “compact” by obstructing and otherwise failing to enforce the Fugitive Slave clause.

The Fugitive Slave clause:

“Copperheads like the New York Times may magisterially declare: “of course, he never fought for slavery.” Well, for what did he fight? State rights? Nonsense. The South cared only for State Rights as a weapon to defend slavery. If nationalism had been a stronger defense of the slave system than particularism, the South would have been as nationalistic in 1861 as it had been in 1812.”

***

David T. Beito is a Research Fellow at the Independent Institute, Professor of History at the University of Alabama, and co-author with Linda Royster Beito of T. R. M. Howard: Doctor, Entrepreneur, Civil Rights Pioneer (Independent Institute, 2018).

Yale University professor William Nordhaus was named a co-recipient of this year’s Nobel (Memorial) Prize in Economic Science for his work on climate change. The award was of particular interest to me because back in 2009 I published an article in The Independent Review offering a thorough analysis and critique of his Dynamic Integrated Model of Climate and the Economy (DICE). At the Institute for Energy Research website, I have explained that Nordhaus’s latest version of his model does not support the United Nations’ current push for aggressive measures to limit global warming. In the present post, I will revisit my 2009 article to showcase three surprising facts about Nordhaus’s DICE model, all of which are very relevant for the climate change policy debate.

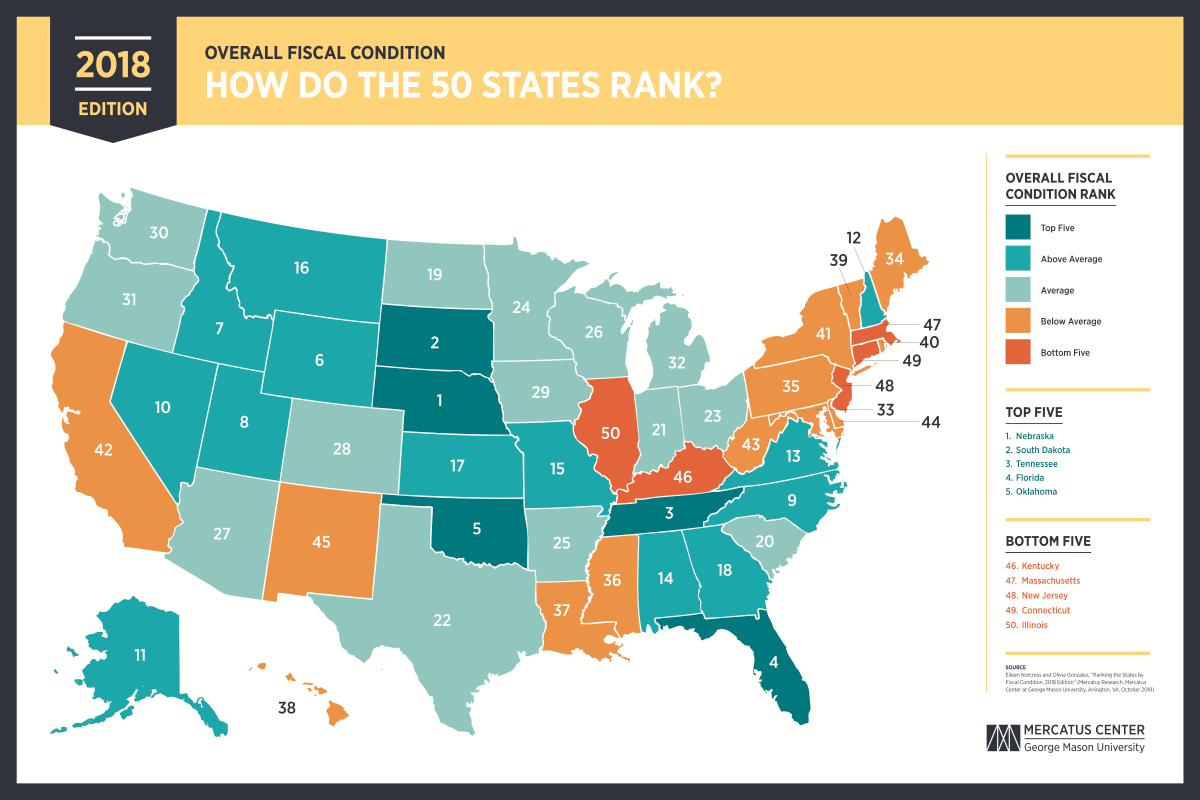

It’s ranking season for comparing the relative health of individual U.S. states! After covering how your state ranks on personal income taxes, it’s now time to dig deeper into your state’s fiscal health, which we can do with the 2018 edition of the Mercatus Center’s State Fiscal Condition Rankings, which were just published earlier this month.

Conducted by Eileen Norcross and Olivia Gonzalez, the 2018 study measures how well state governments within the U.S. are able to meet their short and long-term obligations based on their financial statements. Norcross and Gonzalez paid close attention to the following five measures of fiscal stability, which they combined to produce an overall ranking for the solvency of state governments.

- Cash solvency. Does a state have enough cash on hand to cover its short-term bills?

- Budget solvency. Can a state cover its fiscal year spending with revenues, or does it have a budget short-fall?

- Long-run solvency. Can a state meet its long-term spending commitments? Will there be enough money to cushion it from economic shocks or other long-term fiscal risks?

- Service-level solvency. How large a percentage of personal income are taxes, revenue, and spending? How much “fiscal slack” does a state have to increase spending if citizens demand more services?

- Trust fund solvency. How much debt does a state have? How large are its unfunded pension and healthcare liabilities?

The following map illustrates their results, emphasizing the Top 5 states (Nebraska, South Dakota, Tennessee, Florida, and Oklahoma) and the Bottom 5 states (Kentucky, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Illinois) in the rankings.

Americans have a unique advantage (or disadvantage, depending on how one looks at it) in experiencing their nation’s defense and foreign affairs, namely, that for the great majority such affairs take place “over there” somewhere, often in a place they can’t locate on a map and about which they know approximately nothing. They don’t have to smell the smoke and the decomposing bodies. They don’t have to hide in holes while their homes are demolished by bombs, rockets, and artillery. Because they have so little first-hand experience, they are vulnerable to being bamboozled by what their leaders tell them about what’s going on halfway around the world.

The leaders themselves don’t know much, either, notwithstanding the great sums they expend on gathering and analyzing information. Top leaders more or less ignore this intelligence and make their decisions on more personal, immediate, and political grounds. But they don’t need to know much in any event, because they have great power, and even if they don’t really know much about places X, Y, and Z, they can still drop bombs on those places, claim credit for protecting the American people, and hope the situation does not unravel too visibly before the next election.

***

Robert Higgs is Senior Fellow in Political Economy at the Independent Institute, author or editor of over fourteen Independent books, and Editor at Large of Independent’s quarterly journal The Independent Review.