Frederick Douglass: Lion of Individualist Liberalism

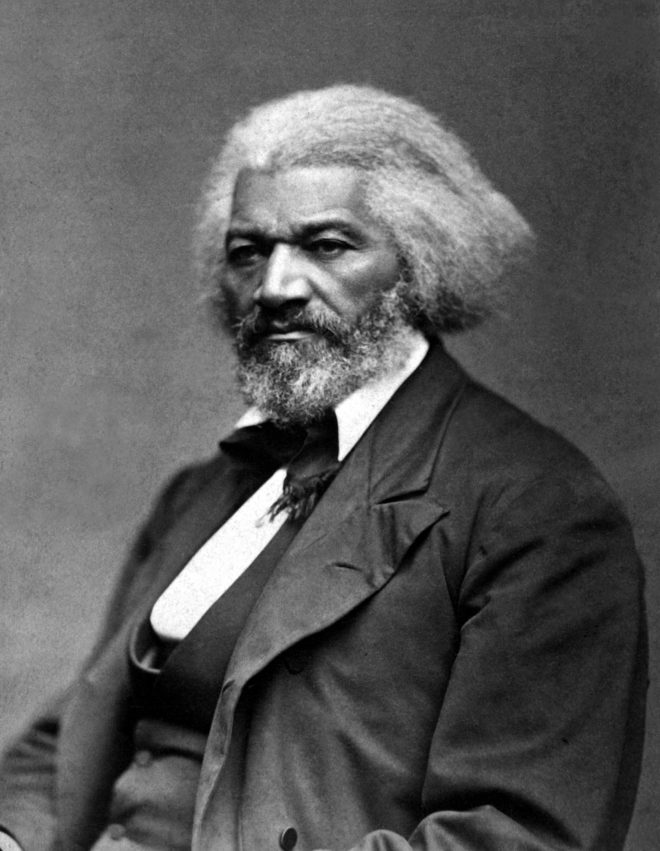

Frederick Douglass, whose bicentennial birthday fell on Valentine’s Day, is one of the great figures in American history, a hero whose legacy is celebrated even by those who might otherwise contest his actual ideas.

Illustrating this truth, the New York Times marked the occasion by publishing a largely negative review of Timothy Sandefur’s new biography, Frederick Douglass: Self-Made Man—a book that depicts the African-American ex-slave and social reformer as a classical liberal who championed individual liberty based upon natural rights, self-reliance, and Rule of Law.

The book reviewer, Yale University historian David W. Blight, criticizes Sandefur and other “conservatives” for “co-opting” Douglass. (Sandefur is a self-described libertarian, but in Blight’s mind, ‘libertarian’ and ‘conservative’ are distinctions without a difference.) In making this complaint, Blight demonstrates his confusion as to the meaning of “the Right” and classical liberalism.

Blight concedes that Douglass was a “radical thinker and a proponent of classic 19th-century political liberalism” who “loved the Declaration of Independence” and “the natural-rights tradition.” On these issues, Blight’s view is consistent with Sandefur’s libertarian interpretation of Douglass.

Yet, Blight goes on to protest that the libertarians (or conservatives—he conflates the two groups) are wrong to co-opt Douglass because the great abolitionist “believed that freedom was safe only with the state and under law.”

But this view of freedom’s security is not one that libertarians would dispute. To say otherwise is to make a classic straw man argument.

As I show in my anthology, Race & Liberty in America: The Essential Reader, the historic civil-rights activists in the classical liberal tradition championed individual freedom under the Rule of Law. And by “law,” they didn’t simply mean statutory “law”—as this obviously made no guarantees for the liberty of slaves before Emancipation, Chinese immigrants banned from entering the United States under the Chinese Exclusion Act, or Japanese-Americans interned at detention centers during World War II under the Roosevelt administration.

Time and again, classical liberals advocated government action to secure life, liberty and property to all regardless of race, color or creed. Hence their commitment to abolitionism and support for liberal immigration policies. Even so, in so many cases, government was the problem—and the solution they sought was to remove government barriers to freedom.

Blight’s review gets two things about political classification especially wrong. First, classical liberalism is neither Left nor Right. Throughout history, classical liberals have extolled “unalienable Rights,” individual freedom from government control, the U.S. Constitution as a guarantor of freedom, color-blind law, and capitalism. These values distinguish classical liberalism from left-wing liberalism, with its emphasis on group rights, equality of outcomes, and hostility to free-market capitalism. They also put classical liberals squarely in opposition to nativists and white supremacists who used the law as a weapon to exclude “undesirable” immigrants or separate the races in the American South.

Second, “libertarianism”—the modern descendant of classical liberalism—is not and never has been a “do-nothing” philosophy. Classic liberals (or libertarians) were activists for abolishing slavery, eradicating segregation, defending immigrants’ rights, passing anti-lynching measures, and much more. Indeed, although they recognized the role that law played in protecting the exercise of liberty, it was the law that so often violated the inalienable rights of Americans. Classical liberals fought slavery, segregation, pernicious immigration quotas, internment, and “affirmative action” because these government measures denied individuals equal protection of the law.

Blight’s conceptual errors may account for why he sometimes badly misreads his subject. He claims, for example, that Douglass loved “the reinvented Constitution—the one rewritten in Washington during Reconstruction, not the one created in Philadelphia in 1789.” This is a gross mischaracterization of Douglass’s views.

Douglass believed that the original Constitution never sanctioned slavery because it was based on consent, a view informed by Lysander Spooner’s Unconstitutionality of Slavery (1845). Any constitutional clause in support of slavery was automatically null and void, Spooner argued, because no slave had ever consented to involuntary servitude. Like many other classical liberals of his day, Douglass used Spooner’s ingenious argument to skewer unjust laws while simultaneously upholding a moral order.

Thus, Douglass denounced American hypocrisy in his famous “Fourth of July” speech (1852) but ended his jeremiad by stating: “Fellow-citizens! there is no matter in respect to which, the people of the North have allowed themselves to be so ruinously imposed upon, as that of the pro-slavery character of the Constitution. In that instrument I hold there is neither warrant, license, nor sanction of the hateful thing; but, interpreted as it ought to be interpreted, the Constitution is a GLORIOUS LIBERTY DOCUMENT. . . .” By its nature as a charter based on consent of the governed, the Constitution is inherently an anti-slavery document.

Blight, the Yale historian, is hardly unique in his misrepresentation of the classical liberal tradition. Indeed, his flawed approach is typical of many progressive writers, who see no conceptual alternative but to divide the polity into Red and Blue, as defined by the two leading political affinities of the moment. Fortunately for America, the writings of Frederick Douglass are always there to remind us that individuals often come in ideological gradients that are often too complex and subtle to fit under common labels, and that they possess inalienable rights that deserve equal protection under the law.

***

Jonathan Bean is a research fellow at the Independent Institute. He is the editor of the book Race & Liberty in America: The Essential Reader.